|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Ecc514 - Orthodox Ukrainian jurisdictions |

|||||||||||||||||||

Lesson 2: Unity prior to the Slavic Expansion - 5Chalcedon (451 C.E.)As we just saw, the Council of Ephesus declared that Mary was truly entitled to be called ‘Mother of God’, thus making it clear that Christ was not just a super-glorified human being. But it remained very difficult for many Christians to see how Christ was both human and divine. They were aided in this dilemma even by Scripture, for of the four Gospels, the first three [the ‘Synoptic’ Gospels] tend, all things being equal, to stress the humanity of Christ, while St. John stresses his divinity.The school of Antioch also emphasized his humanity, the school of Alexandria his divinity. In addition, the Emperor in Constantinople was concerned to preserve religious unity in the Empire, and believers tended to support (or not support) him out of political, rather than religious, convictions. The result was the calling of another great Council of the Church, in 451, at Chalcedon, which was opposite Constantinople. A monk called Eutyches popularised a teaching that Christ had only one nature – a kind of mixed divine-human. The implications of this for soteriology were tremendous. It would mean that Christ could not redeem humanity, because he was not fully human. And it would mean that he did not have the power to redeem, because he was not fully divine. The Chalcedon Council came up with the last of the great statements of early Christian belief, reaffirming that Christ "is God, of the Substance of the Father … and he is Man, of the Substance of his Mother. Although he be God and Man, yet he is not two, but one Christ."

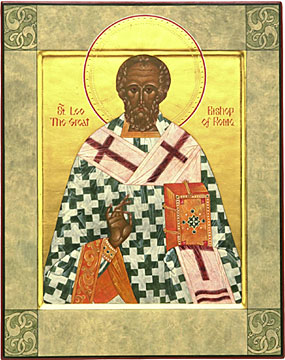

The same holds true for popes. This was yet another council the Roman Pope did not attend, but on this occasion, as with others he contributed letters to it. Pope St. Leo the Great sent a document, known as the "Tome of Leo", which was read outloud and allegedly caused the delegates to exclaim "Peter has spoken through Leo!" Roman Catholics love this. But this exclamation was due more to the flavor of its confession, which emphasized the nature and divinity of the Lord reminiscent of Mathew 16, than it served to acknowledge infallibility of the the Roman Pontiff, which up to that point we have no trace of in any Council records. It was a gratuitous comment made a people who had not anticipated how it would later be construed. Itt has been used as a proof-text by Rome concerning a jurisdictional power that went beyond the practical power of the metropolea to a dogmatic supremacy that had no respect to it. But that was just one of the problems. Belief in the doctrine of Chalcedon was declared to be necessary for salvation, but alas not all Christians believed it, partly because of the political rivalries under the surface, but also because a more precise Christology was really called for that would not risk the unity of the two natures as one incarnate nature in Christ. Rightly or wrongly It caused the breakaway of many of the early Churches of the East – Ethiopia, Egypt, Armenia, some of the churches of India – and formal reconciliation has only been partly achieved even today. But schizm is not so simple as "here today gone tomorrow." And in fact, to call something a Great Ecumenical Council or not, does not immediately equate to acceptance. Subsequent centuries would produce Anti-Chalcedonians and unifiers who would be anathematized based on the accusation that they were both Netsorian and Eutychian, almost a contradiction in terms. At least one of them ascended to the Patriarchate, enouraged by a tradition of Emperors, starting with Zeno in 476, who were not happy with the schizm. Zeno issued decrees in his Henoticon, which affirmed the first three Councils saying 'Anyone who thought or thinks otherwise, either in Chalcedon or at any other Council, we anathematize.' No doctrine was given in this controversial document which did little more than reiterate what was already said in the first three Councils, while holding off any comment on Chalcedon outside of a fateful anathematization of Leo's Tome.

While ecclesiological borders were certainly defined through Canons, sides were taken over confused language and misunderstanding. Many took sides in the controversy and did not have unity at heart. By 511 C.E. the new Emperor Anastasius, who was Anti-Chalcedonian convened a Synod of Bishops that deposed and anathematized the Patriarch of Constantinople, Flavian, for failing to anathemetize Chalcedon. Flavian was replaced by Severus. Severus was in turn anathemetized by the Pro-Chalcedonians after he had affirmed the Henoticon. Despite his fate as a loser in the battle for Truth in the Orthodox Church, Severus was clearly on a middle ground, not of compromise but of deeper understanding. He didn't just anathematize Chalcedon. He also anathematized both Nestorius and Eutyches. And he anathematized Deodore and Theodore of Tarsus too. His books were later burned. But we do have some surviving letters that indicate his true Christology. He emphasized the particularity of natures, defining them as "without confusion" yet united as one nature in the incarnation.

So it is that the church operated on misunderstanding, anathematizing even a great saint such as Severus (an ironic name as it is rendered in English). They called Councils but were not really attempting and perhaps not willing to work out differences. They were not interested in attempts at unity. The results of their decisions were to depose their patriarchs. Sergius was fortunate to have escaped Constantinople with his life to live out his remaining years as a monk. Hostility marked the age. Perhaps, in these last days people will be more inclined to recognize their error. History has not been so kind. One sad result of these rivalries was to be the loss of much Christian heritage to the advance of Islam: the Arabs proved much more tolerant of religious divisions than the Emperors, and many gratefully accepted their rule, and their faith. By the year 800 much of the territory which had produced these ancient statements of Christian belief had been lost to Christ for ever. Meanwhile, the Non-Chalcedonian Christians, as they prefer to be called, rather than Anti-Chalcedonian, offer up a very reasonable reason for their rejection of this Council. They do not believe it was "ecumenical" even with its 520 bishops. Click here for the "rest of the story" (a Non-Chalcedonian perspective). In their eyes, the church was ecumenical up to this point. Subsequent supposedly "Great" Ecumenical Councils were made invalid in their absence, as to be "ecumenical" means to teach what has been taught everywhere by all at all times, and at this Council the unity of Christ's nature(s) was not clarified. Nevertheless, the Councils did continue and shaped the very Pro-Chalcedonian Ecclesiastically defined Christianity that would eventually dominate Rus, the Ukraine and all of Russia...

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

But everything is not so rosey. And quite frankly, it is very questionable whether Emperors, however well intentioned, are really capable of creating unity.

But everything is not so rosey. And quite frankly, it is very questionable whether Emperors, however well intentioned, are really capable of creating unity.  Henoticon actually means "icon of unity." Despite the anathema, what concerned Zeno was unity. Can the body of Christ be divided? Was it defined by the pronunciation of anathemas at Chalcedon? If so, how did the Non-Chalcedonians, for whatever reason, fit in as the body of Christ? Convoluted notions of the mixture of divinity and humanity in Christ were paralleled by convoluted notions of the mixture of Christ in his church.

Henoticon actually means "icon of unity." Despite the anathema, what concerned Zeno was unity. Can the body of Christ be divided? Was it defined by the pronunciation of anathemas at Chalcedon? If so, how did the Non-Chalcedonians, for whatever reason, fit in as the body of Christ? Convoluted notions of the mixture of divinity and humanity in Christ were paralleled by convoluted notions of the mixture of Christ in his church.