|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Ecc514 - Orthodox Ukrainian jurisdictions |

|||||||||||||||||||

Lesson 2: Unity prior to the Slavic Expansion - 7Constantinople (680 C.E.)

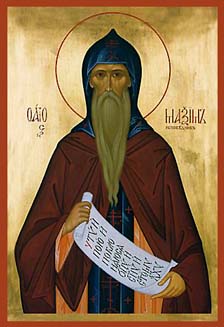

Monophysitism (which means "one nature"), in spite of the decisions of the Fifth Ecumenical Council and in spite of the strict laws and other repressive measures against it by subsequent Emperors, continued to be a serious disturbance to both Church and State. It actually was used as the foundation for the creation of new and independent Churches such as the Armenian, Abyssinian, and others. Not long afterwards a refinement on monophysitism brought on a new controversy, even though it was born of good intentions. As a result of the reconciliatory endeavours of Emperor Herakleios for the purpose of bringing back the Armenians to the Orthodox Church, a new teaching in regard to the Person of Christ began to spread. By it, there is only one will in the God-man Christ. The word "thelos" means will - hence this teaching was called 'monothelitism' and was originally proposed as a midpoint between Monophysitism and Orthodoxy designed to bring back the Monophysites at a time the empire was threatened by the Persians and later by the Mohammedans. Both the Patriarch of Constantinople Sergios and Pope Honorius accepted the Emperor's formula by which there were two natures in Christ but only one mode of 'activity'. But in a statement of doctrine, the Pope used the unfortunate expression 'of one will' in Christ which from that point on replaced the expedient 'one energy' agreed upon by both parties. It isn't such a good idea to let Emperor's determine doctrine purely for the sake of reconciliation. What is needed for unity is a spirit of holiness and repentance. We all know from history that after some tumultuous developments, the monotheletic controversy was finally resolved by the Sixth Ecumenical Council. Monothelitism was condemned together with its adherents. Lost in the story tends to be the fact that whatever political blunders may have been the basis for just complaints by Non-Chalcedonians that would have caused them to reject previous Councils, the spirit of sanctity may just have prevailed as the driving force in the Sixth Great Ecumenical Council so that it was not an Emperor glueing together a divided episcopacy, but an episcopacy that was drawing back again to the mind of Christ under the leadership of Maximus, known as the Confessor, for his great holiness. In all it can be said that there were certainly differing wills, but unity in Christ. And no one understanding the difficulty of working out the mystery of salvation failed to understand the dual nature of mankind, which is at once drawn by the will of the flesh, and again by the new nature of the spirit - again a core component of salvation. The Council proclaimed that "Christ had two natures with two activities: as God working miracles, rising from the dead and ascending into heaven; as Man, performing the ordinary acts of daily life. Each nature exercises its own free will". Christ's divine nature had a specific task to perform and so did His human, without being confused nor subjected to any change or working against each other. "The two distinct natures (and related to them - activities) were mystically united in the one Divine Person of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ". Sergius, Pyrrhus, Paul, Peter, Pope Honorius, and Cyrus favored monotheletism and, still among the living, were anathematised. St. Maximos the Confessor, filled with the Spirit and mercy of the Lord led this council in the Spirit of prophecy. Emperor Constantine IV had only intended to convene a local Council, but on inviting several Metropolitans and bishops, word spread in a move of the Holy Spirit that trumped the Emperor's control. He had written Pope Agatho on the subject. All five ecumenical patriarchates were represented, even though Jerusalem and Alexandria were then dominated by Muslim threats, and had to send delegates. THE QUINISEXT COUNCILBetween the Sixth and Seventh Councils is what is known as the Quinisext Council of Trullo and deserves special mention. It was called by Justinian II in 692. Both the Fifth and Sixth Ecumenical Councils fully occupied their time with the Christological problem and issued no canons pertaining to ecclesiastical government and order. Actually, the Quinisext may be considered to be the continuation of all the preceding Ecumenical Councils inasmuch as by its 2nd canon it received and ratified all of their canons and decisions. It also ratified the so-called "Eighty-five Apostolic Canons", the canons of local synods, and the most important of the canons of the principal Fathers of the Church, thus empowering all of them with Ecumenical authority. The disciplinary canons of the Quinisext, however, were not accepted by the Pope, and even though most of them were not completely observed in the East, they contributed appreciably to the widening of differences between East and West. For example, canons 13, 30, and 48 relating to the marital status of the clergy, others regulating the age of ordination, and still others relating to canonical impediments to matrimony, were contrary to already established different practices in the West that the Roman See did not wish to change on directives from the Quinisext Council. However, the same Council tabulated by its 6th canon a shaky practice in the East by which marriage could not be contracted after one had been ordained in any one of the three ranks of priesthood. Thus, and for the first time, priesthood as a sacrament was accorded precedence and superiority over the sacrament of matrimony. And though there is no dogmatic justification for this doctrinal demoting of the sacrament of matrimony, the prohibition of marriage after ordination continues in the Orthodox Church to this day. We can see then in this Quinisext Council the work of bishops writing laws to accomplish conformity and rule, for whatever purposes, rather than the Holy Spirit, dictating doctrine to accomplish salvation, though there were certainly practical purposes which may have had the safeguarding of the church in mind.

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

The Sixth Ecumenical Council met in Constantinople in 680 AD and was convened by Emperor Constantine IV (Pogonatos) and St. Martin (Pope of Rome). It was not much larger than the Council of Chalcedon, attended by just 170 bishops. But that it was just as large was significant, because it was no any Emperor's doing.

The Sixth Ecumenical Council met in Constantinople in 680 AD and was convened by Emperor Constantine IV (Pogonatos) and St. Martin (Pope of Rome). It was not much larger than the Council of Chalcedon, attended by just 170 bishops. But that it was just as large was significant, because it was no any Emperor's doing.