|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Lesson 2: Unity prior to the Slavic Expansion - 8Nicaea (787 C.E.)

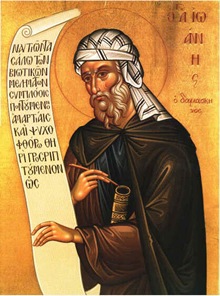

Men resorted to blind faith and law rather than to revelation. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that they rejected Christ, most especially in North Africa and turned to Islam, which did not require either a Jewish Law to fulfill or an incarnate God. Or they rejected Islam and turned back to the Old Covenant, trying to preserve some human image of Christ. For this reason they became increasingly legalistic, which should not be too surprising, since even where heresy did not prevail, the church had become extremely wordly and caught up in the grab for control and church imposed uniformity, and had exhibited the tendency to hate, even anathematizing the dead at Council. It was in this very human, (read sinful and unenlightened) milieu that the Christian world resorted to destroying pictures of saints and images of Bible stories called icons on the basis that they were idols. Also opposed to icons were those who held the divinity of Jesus at the expense of the fulness of his real humanity. For them, icons were even more base and material than the flesh He himself supposedly took on. Nothing can be more human than a portrait! In the 8th century a wave of "remote-God" feeling seems to have swept over parts of the East, simultaneous with a similar movement in Islam. Thou shalt worship God alone. Thous shalt place no image before Me (Ex 20; Dt 5). The commandment was clear. So was the lack of growth in Christ. We again resorted to slavery under the Law. We were no longer friends who communed with Him in intimacy. In 726 soldiers tore town an image of Christ over the gate of the imperial palace at Constantinople, and a riot ensued. In general, the monks supported the use of icons but the army opposed it. The Emperor, Leo III, had saved the city from the Arabs and, as a hater of idolatry, was very suspicious of icons. There were, inevitably, abuses: icons which wept, which bled, which spoke. The emperor decided to eliminate the whole practice. The ‘iconoclasts’ (icon-breakers) clashed with the ‘iconodules’ (icon-venerators) and a grave persecution ensued, especially under Leo III’s son, Constantine V, who died in 775. Already in 754 a Council had forbidden the use of icons, saying that Christ was seen only under the forms of bread and wine. Those who longed for a greater communion with the Lord and who recognized the love of God in the church in all ages were forced to explain and defend their use of icons in worship. How was it that these images were not being worshipped, especially those which contained the image of Christ? In the tragedy of human experience many zealous individuals killed Christians who worshipped with icons. Much valuable property was destroyed, along with many precious memories. As a human, Christ had a physical appearance. Could an image be made of him as an aid to worship? The earliest Christians – apart, of course, from those who actually knew and saw Jesus in the flesh – did not know what he looked like, and did not seem to mind not knowing. They accepted in faith that Jesus was still truly alive. On the other hand, many of the early saints of the Church, the first martyrs, were people whom they had known day by day; their physical appearance was known to them, and they found it helpful to remember them (rather as we may keep photographs of people dear to us in our wallet). Thus developed the use of images, pictures, as aids to worship. Increasingly stylised in form, they were known as icons, and the tradition of using them has continued in the East, while the West has branched off in a different direction, to include statues and more modern renditions. In 787, Constantine’s widow Irene, as regent, called a Council of the Church, at Nicaea (the 7th Ecumenical Council, held in the same place as the first). The council defended the use of images, for Christ in his humanity had had an image. It established rules for their use, however; they could not be three-dimensional, only flat (Western practice has moved away from this), so as to avoid excessive ‘life-likeness’ which might be seen to encourage idolatry. One of the champions of the 2nd Council of Nicaea was St. John of Damascus, who had died in 749, but whose enthusiastic support of the use of icons was brought in ‘evidence’, along with the teaching of St. Basil, that "when we give honour to the image, we worship the prototype". Had the iconoclasts prevailed, then one aid to understanding the humanity of Christ would have been lost – and churches, East and West, would have looked very different. This Council dealt predominantly with the controversy regarding icons and their place in Orthodox worship. It was convened in Nicaea in 787 by Empress Irene at the request of Thrasios, Patriarch of Constantinople. The Council was attended by 367 bishops and was perhaps the most ecumenical Council of the Seven considered Great. Despite this, the Emperor Charlemagne refused to recognise it not only as Ecumenical but altogether. He disapproved of its decision for venerating the icons. In fact, as a result of his hostility, a synod at Frankfurt in 794 condemned the veneration of icons and rejected the entire Council. And it was only by the end of the 9th century that the Council was recognised in the West at all. Further, the West disagreed witht its rules, regarding flat icons, that were contrary to the established practices of the Roman Church, which was unwilling to give up its beloved statues. You might think the statues would have been more offensive than the icons. Not so. Almost a century before this, the iconoclastic controversy had once more shaken the foundations of both Church and State in the empire. Excessive religious respect and the ascribed miracles to icons by some members of society, approached the point of worship (due only to God) and idolatry. This instigated excesses at the other extreme by which icons were completely taken out of the liturgical life of the Church by the Iconoclasts. The Iconophilles, on the other-hand, believed that icons served to preserve the doctrinal teachings of the Church; they considered icons to be man's dynamic way of expressing the divine through art and beauty. The Council decided on a doctrine by which icons should be venerated (προσκυνησειω) but not worshipped (λατρειω). The word "idolatry" only comes from this latter word. In answering the Empress' invitation to the Council, Pope Hadrian replied with a letter in which he also held the position of extending veneration to icons but not worship, the last befitting only God. The decree of the Council for restoring icons to churches added an important clause which still stands at the foundation of the rationale for using and venerating icons in the Orthodox Church to this very day: "We define that the holy icons, whether in colour, mosaic, or some other material, should be exhibited in the holy churches of God, on the sacred vessels and liturgical vestments, on the walls, furnishings, and in houses and along the roads, namely the icons of our Lord God and Saviour Jesus Christ, that of our Lady the Theotokos, those of the venerable angels and those of all saintly people. Whenever these representations are contemplated, they will cause those who look at them to commemorate and love their prototype. We define also that they should be kissed and that they are an object of veneration and honour (timitiki proskynisis), but not of real worship (latreia), which is reserved for Him Who is the subject of our faith and is proper for the divine nature. The veneration accorded to an icon is in effect transmitted to the prototype; he who venerates the icon, venerated in it the reality for which it stands". The Council also issued canons relating to administrative and disciplinary matters. They condemned simony (ordination for payment), the election of bishops by secular authority, and the erecting of co-ed monasteries. The Emperors were opposed but Empress Theodora was the heroine. An Endemousa (Regional) Synod was called in Constantinople in 843. Under Empress Theodora. The veneration of icons was solemnly proclaimed at the St. Sophia's Cathedral. Monks and clergy came in procession and restored the icons in their rightful place. The day was called "Triumph of Orthodoxy." Since that time, this event is commemorated yearly with a special service on the first Sunday of Lent, the "Sunday of Orthodoxy". The Council of 787 is the last to be recognised by the churches of both East and West. In 1054 came the great East/West split, which subsequent Councils of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches (Lyons 1274, Florence 1439) tried to resolve, but unsuccessfully. This was the core set of beliefs that were delivered by the time Christianity headed up to Russia through Kiev. It was a triumphant Orthodoxy, packed with icons and canons, and very specific doctrines, which would not change much at all in the subsequent 1000 years, outside of being influenced to some extent by the West.

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

We have seen that the early Councils of the Church established that Christ was truly human and truly divine, and that the one person, Son of God, had two natures: one human and one divine and how this effected soteriology. The less in common Christ was with man in men's thinking the more likely it was that man would resort to an alienated mentality with respect to salvation. If Christ did not save man by becoming truly human while being the One who could save him because he was truly Divine then there must have been some other mechanism by which men are saved.

We have seen that the early Councils of the Church established that Christ was truly human and truly divine, and that the one person, Son of God, had two natures: one human and one divine and how this effected soteriology. The less in common Christ was with man in men's thinking the more likely it was that man would resort to an alienated mentality with respect to salvation. If Christ did not save man by becoming truly human while being the One who could save him because he was truly Divine then there must have been some other mechanism by which men are saved.